Making the trivial…nontrivial: How Phil Edwards makes attention-getting videos

How does former Vox producer Phil Edwards make such compelling explainer videos about seemingly trifling topics?

Phil Edwards makes videos that, unexpectedly, keep us watching.

From his work at Vox: a video on World War II graffiti earned 4.4. million views. Modern plastic/vinyl siding: 2.2 million watched it. Medieval marginalia: 3.4 million. The Wingdings font: 4.4 million. (For context: YouTube says Vox’s videos earn an average of 2 million views.)

Phil Edwards made 146 videos during his eight years with Vox’s vaunted team before he and other colleagues were laid off in November. These days Edwards produces his own channel with the following description: “History and personal videos. Business. Tech. French fries. Shoes. Civil war balloons.” Its content ranges from cinema technology (greenscreen 2.0,), to food (oreos! Turtle soup!) to history (Rosie the Riveter), to design (the oval office, the NASA logo), and video games (Pac-man). On YouTube, Phil Edwards is officially the nerd’s nerd.

But Edwards isn’t just good at finding unexpected stories. He makes millions of viewers care enough to watch for the full nine to fifteen minutes his videos generally last.

And he cranks one out every two weeks. I interviewed Edwards to find out: How?

1. Choose a story. Where does Edwards get his ideas? “Random things that people get worked up about but aren't curious about,” he says. “Comments on other videos, weird things I just stumble into in books. Hodgepodge!”

Longtime Vox colleague Joss Fong admires his ability to uncover fresh topics. “I have no idea how he finds his stories or how he reads all of the books he reads,” Fong wrote in response to questions I emailed her. “Sometimes it can seem like every publication is doing different versions of the same things, and then there's Phil finding dozens of topics that nobody else has touched. That may be a disadvantage in any given news cycle, but over time it builds confidence in viewers that his videos will introduce us to something we didn't know about.”

When you’re interested in almost anything, it can be tricky to select which story to tell. YouTube provides dozens of metrics on each published video. But using this data to predict what will attract viewers next is still the central challenge of online video. (As they say in Hollywood about what will sell: “Nobody knows anything.”)

Edwards says he’s still trying to improve his “idea approval process” to increase his chances of making winners. He knew that audiences might recognize the iconic photo of Earthrise he explored in a recent video, but “had no idea” the piece would resonate with so many (1.4 million views and counting.) But Edwards called another video, on the history of wheelies “a huge flop” as it garnered fewer than 50K views. (I thought it was good! -Eli) Before he published it though, he told friends about the idea and they’d give him a “blank stare” he says. “I should have been able to read the tea leaves.”

So the challenge, then, is for Edwards to find almost-marginal stories -- and convince us they aren’t too marginal. To gauge potential audience interest as he considers a story, he makes a thumbnail image and headline and shares it with a private discord channel with other YouTube creators. “It has to have a thumbnail in a headline that are really clicky,” he says, with a story “that's really hopefully clicky and relevant.” Only then does he greenlight an idea.

2. Research like mad, collect visuals and write.

“The research is the best part,” Edwards told me. He spends the first week of each video’s two week cycle researching, collecting assets and writing. For the Earthrise video, “I was kind of casting about for a NASA photography story,” he says, even considering a full video on the 1960’s Hasselblad camera. He eventually realized the Earthrise photo itself was the best focus.

Edwards scours the web for essential secondary and primary sources, seeking what he calls the “Rosetta stone” for each video. That’s a key document, he says, that provides backstory and arguments for his narrative line. Here, for the Earthrise piece, it was a PHD dissertation on astronaut photography. Here, for a piece on the history of operating rooms, it was a 1914 medical article. (And, hallelujah, unlike many digital video producers, he shares his sources in the video descriptions.)

When the material he’s collecting start to include facts he’s read in other documents, he says, his research is complete, and it’s time to start collecting the videos, audio, documents and photos he’ll need for his video.

Then he starts to write. Here’s a bit of script from his Earthrise video showing how central the visuals are to his writing approach:

Producing for Vox, he usually included an interview in his explainers, but for his own channel he hasn’t done that much, he says. More important is adding narrative interest by constantly playing with story: breaking the fourth wall, introducing side quests, backstories, interruptions, visual gags, layering audio. And he’ll modify ideas from anyone. Vox pieces on shipping containers and an iconic mid-century office building were inspired, he says, by the storytelling style of superstar YouTuber Ryan Trahan, whose videos usually include wild adventures like traveling across the U.S. on one penny.

Edwards is usually a character in his videos, and his tone includes self deprecation that can sometimes feel excessive. But often it’s just genuine and sweet. He insinuates that he likes McDonald fries despite their uncoolness. He dad-joke-ingly uses a toy train to illustrate a famous train crash. He chides himself over flying from his home in Virginia to San Francisco to see a gas station. And when his camera falls down he publishes the shot.

The message the viewer gets, I think, is ‘Hey I think it’s cool to nerd out about why Reebok is called Reebok so don’t feel bad about enjoying it.’

3. Shoot, edit, animate, publish.

After he’s finalized the script and collected a ton of assets, he’s got about five days to actually produce the video. “I just race like a madman through the rest,” he says.

With practice he’s consistently improved his shooting, lighting, editing, animation and sound design over the nine years he’s been producing videos – a testament to the power of sticking with it. His videos’ production quality benefits from a zeal to get better. “I was so upset about my graphics and how they looked,” he said during a behind-the-scenes piece about improving his on-screen text and animations. So, during the two hours a day of naptime during the pandemic he had during parental leave he delved into making some templates and a redesign.

Not only are his stories unexpected, but he tells them in visually unique ways. His “Why I left X ” video ingeniously broke with convention (see MatPat’s “Goodbye Internet”, Cleo Abram’s Why I left Vox, Johnny Harris’s VOX BORDERS IS CANCELED ) and delivered a hilarious and even touching send up to the iconic cards scene in Love Actually:

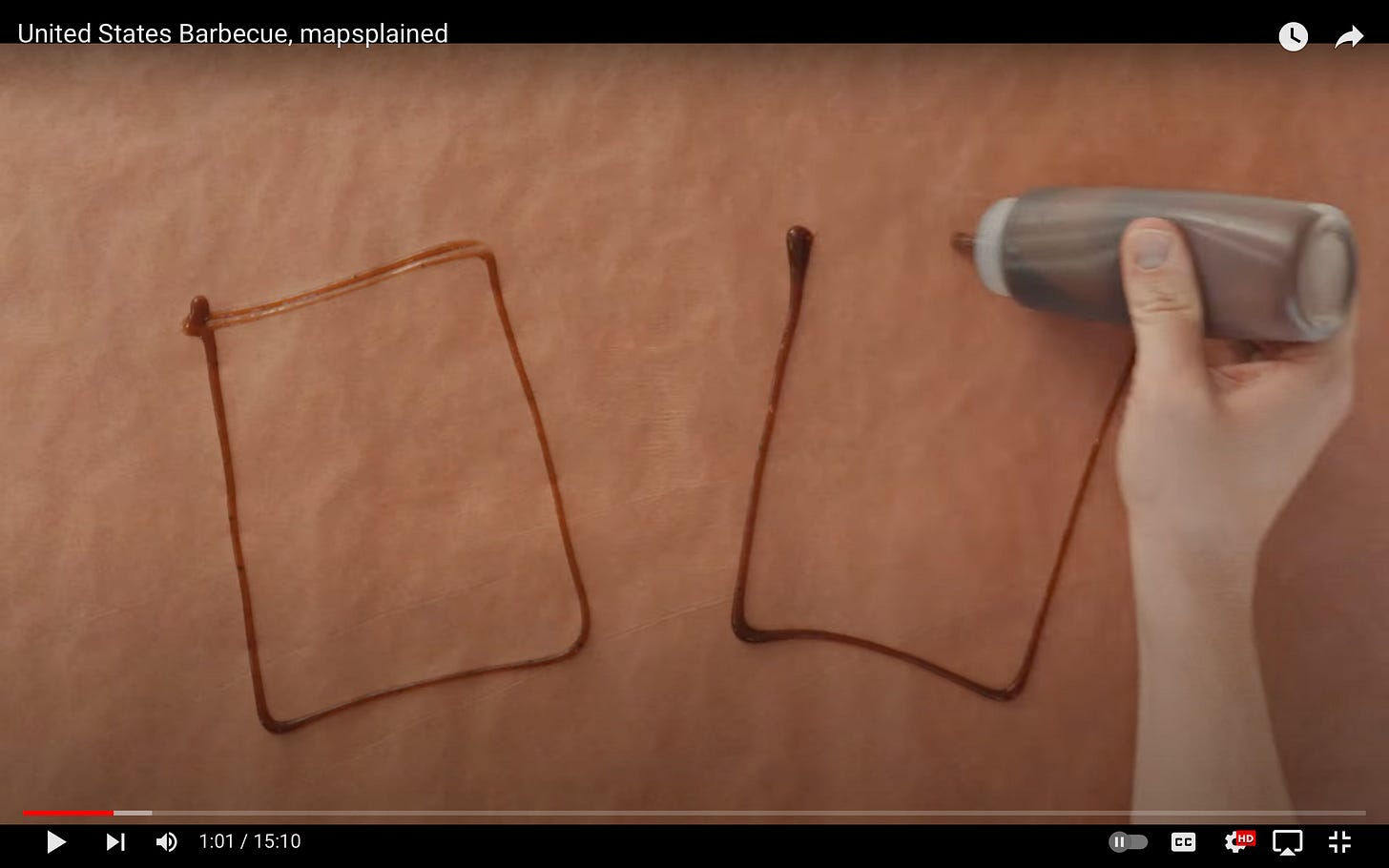

See how Edwards brings to life dusty archival documents in a piece on how the US military fought venereal disease during WWII. Period reports, statistical charts and old footage (all public domain!) provide plenty of grist for the mill. The motion and pace from his animation gives the story visual interest and momentum. Check out his animated timeline here… And, in another video, how he draws shapes with barbecue sauce on brown kraft paper on camera to create an image of two barbecue restaurants.

Touches like that add visual richness to explainers that, in less talented hands, could feel like a video book report.

4. Experiment and constantly improve. Joss Fong considers Edwards “a perpetual autodidact,” she says, adding: “It's painful for a lot of us to try to learn new techniques, especially as we get older and more tired, but Phil has a real appetite for picking up new gear and new software, just to see what he can do with it.”

In a recent video on French fries, Edwards went to the trouble of animating a serving of fries with 3D software just to make a shot comparing McDonalds and Burger King more interesting.

Then again, two months before, he animated that toy from the train crash video to allow for dramatic shots of the catastrophe. In this piece on game shows, Edwards used the gaming software Unreal Engine to animate shadowy images of quiz show contestants and in-studio crowds. Much of the piece relied on old television footage and newspaper clippings, but the animations added a spooky element that fit with the deception theme so it didn’t just feel like an archive dump.

5. Be flexible

Fong thinks Edwards’ most important attributes aren’t his writing abilities, technical skills, or even his creative approaches to video. His personality, she says, makes him successful. “He has a lot of grit, he's self-sufficient, not too precious, and has a huge range of interests -- pretty much exactly who you want to be to make it on YouTube,” she says.

Now Edwards face a new challenge. At Vox, his eclectic videos focused on history and culture, rounding out a channel heavy in politics, public health, and international conflict. Now that he’s creating his own channel, honing his brand as a storyteller will help him attract and keep a consistent audience. Stick to history? Follow the news cycle? For example, in February, he was considering a piece on genetics company 23andme and its declining stock. “I'm like, well that's a kind of a news story, what normal people are interested in. It's not a super esoteric topic,” he said. Which is to say: are some stories not trivial enough for his audience? (In the end he opted not to do it).

Edwards says he’ll start soon including ads in his videos to help pay the bills. But despite his success, he struggles a bit with recognition. He displays his silver YouTube play button here in the intro to his Earthrise piece -- but on its side, in the top left corner.

In an interview with Patreon CEO Jack Conte, by the same token, he continually deferred to other creators, and in his how-I-got-my-Vox-job video he compared himself to famous “lackeys” that made it not through talent but through the force of hard work. In his goodbye Vox video Edwards wrote “With any luck, by next year/ I’ll be a star youTuber.”

But that’s already happened. Because if anyone in this business has shown that you make your own luck, it’s Edwards.

RECENT GOOD EXPLAINERS

AI will remake IP: The New Yorker’s Louis Menand, in his dry and frank style, walks us through the history of copyright and how AI is taking the law into uncharted waters:

A.I. is only doing what I do when I write a poem. It is reviewing all the poems it has encountered and using them to make something new. A.I. just “remembers” far more poems than I can, and it makes new poems a lot faster than I ever could. I don’t need permission to read those older poems. Why should ChatGPT?

I learned that LLM’s (like ChatGPT) predict not sentences but “tokens” and that the standard royalty for a three minute song if you sell a cover is $0.15.

Everyone’s Covid Is Different: Alice Park’s piece on Covid nicely spells out for Time. Why, she asks, do some people keep getting the virus and others not?

At the beginning of the pandemic researchers thought that genes only explained 1% of an individual’s chance of getting the virus. I learned that data from 12,000 infected New Yorkers suggest that genes may determine up to 70% of our vulnerability to Covid.

Taylor Swift has become a brand like Marvel: Ben Lindbergh explains in a career assessment for The Ringer. I learned just how tightly Swift controls not just her image but also her narrative. Oh and here’s why Swift hasn’t headlined the Super Bowl.

Thanks for reading!

Eli

The Explainers is a monthly newsletter exploring explanatory media. I am a science video producer in Washington DC — check out my website, elikintisch.com to learn more and connect.