Storytelling with Vertical Video

5/31/19 edition of TrueTube: Your guide to digital nonfiction video

By Eli Kintisch

In Focus: Nonfiction Storytelling in the Era of Snap

Videographer Armando Aparicio was “hurting for work” last year, he says, when he heard about a possible assignment for Univision, the Spanish-language mega-network. But he said no. The reason? Producers wanted him to make an episode of a new show released on Facebook in vertical format. “I kind of hated vertical video,” says the Los Angeles based filmmaker. Having built a reputation for himself through work for The Nation, The Intercept and others, he was worried that clients would start requesting future projects in vertical. “I’m dedicated to my work and I didn’t want to see vertical video succeed,” he says. In a world with no shortage of vitriol for vertical video, that’s an all-too common sentiment.

Vertical video can be unpleasing to the eye…but it’s becoming ubiquitous

Aparicio eventually relented, though, and has gone on to make several episodes of Univision’s show Real America with Jorge Ramos, which is shot and edited for vertical format exclusively.

Horizontal video and film isn’t going anywhere. But Real America is one of several forays into vertical video by journalism heavyweights. Vertical-first is everywhere now, driven by the explosion of video on vertically scrolling apps like on Snapchat, Facebook and Instagram. And lots of publishers, like Great Big Story, are taking videos shot and cut in the horizontal format for YouTube or broadcast television and editing them into vertical or square orientation for additional publishing on the mobile apps. On Netflix’s phone apps, for example, shows and movies are watched horizontally, though previews play vertically, filling the phone’s screen. There’s a film festival for vertical. Samsung’s even designed a vertical TV.

Katoomba, Australia hosts a biennial vertical film festival

So how did the vertical challenge to the horizontal status quo arise? Digital video derived visually from TV, which derived from movies, which derived from live plays on stage. There actors and scenery are generally arrayed horizontally, since our eyes scan a visual field left and right. The entertainment industry has for seventy years sought to recreate the expansiveness of “landscape” (vs. dull “portrait”) imagery first in movie theaters and then in our homes, with ultrawide televisions. “The stuff we expect to take us somewhere…we still want it wide,” says Adam Freelander:

But the fact that we’re “hardwired to interpret film as wide” may be as much about culture as biology, says British filmmaker and critic Charlie Lyne. Long before the cell phone, he says, filmmakers were experimenting with challenges to the traditional aspect ratio:

In a bygone world of only horizontal movie screens and television sets, innovative frames often didn’t fill the rectangles onto which they were projected. That left “the viewer staring at the blackness surrounding the frame, wondering what they’re missing,” says Lyne in his essay.

But now that’s changed. If media is traditionally formatted to fit our eyes, the mobile video revolution has been built instead around our hands, which hold phones vertically. Four billion people now have a vertical video screen in their pocket at all times.

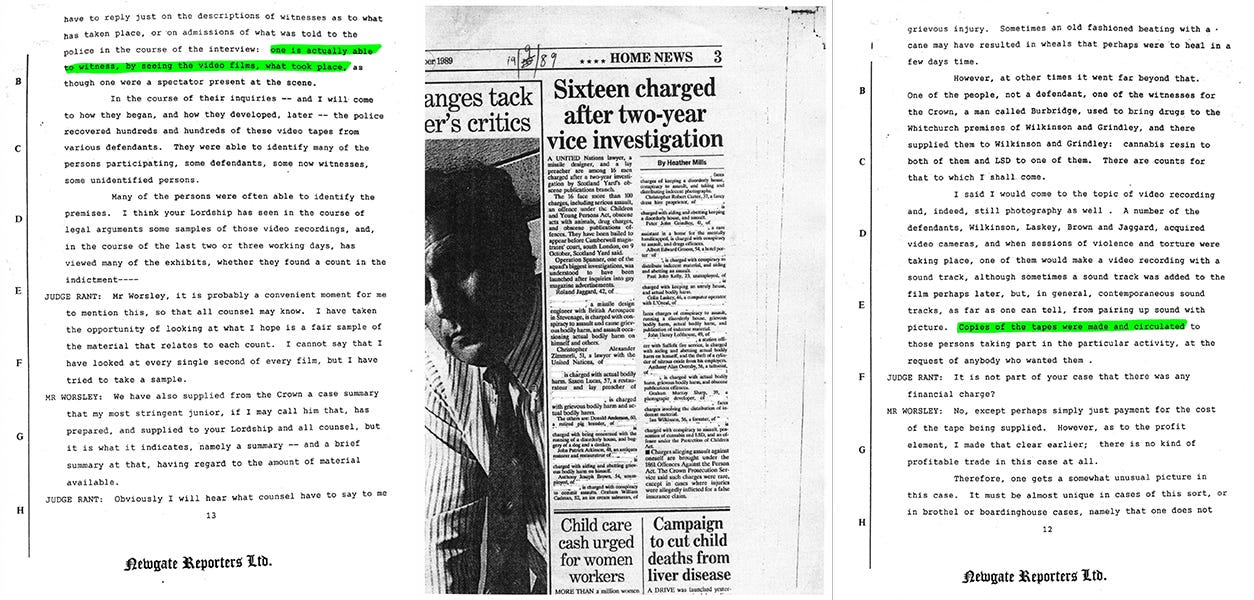

And that’s inspiring new forms. Some topics lend themselves naturally to the vertical format, says Lyne. Last year he released the 15-minute documentary “Lasting Marks, which explores a British police investigation in 1987 into the private sexual activities of gay men. Audio from interviews with a few of those prosecuted in the case forms the backbone of Lyne’s film. But edited vertically, its visuals rely almost entirely on images of case documents like court transcripts, printed on standard European office paper that encompasses the frame.

Eerily sterile documents intersperse with lurid news clippings in Lasting Marks

“It felt natural for the film to have the same format as the documents themselves,” he says. By filling the screen with the entire document, the viewer can see underlined or highlighted passages in context. He avoids zooming in to key lines or making other parts of the text blurry. Lyne dislikes such techniques, commonly used in news videos, since they’re “absolutely prescriptive with how people consume the material.”

Other filmmakers are using vertical video to more creatively fill the screen, and to create strong connections with viewers. Vertical video “creates something very personal, that sits in the palm of the hand,” says Aparicio. The quintessential vertical video, popularized on hundreds of millions of Vines, TikToks, Instagram videos and Snapchats, is a person speaking directly into a forward-facing camera on their phone. That’s the FaceTime-level-of-intimacy with their audience that Univision has sought with Real America, and interviews can pack real power when the subject’s face fills the screen.

Ramos says in promotional material for the show that its journalism is enhanced by the immediacy that vertical video has come to convey. "This is the first time in my life that I have recorded stories with my cell phone in vertical format," he says. "It gives me the freedom and movement that I've never had before. It's journalism with a point of view and that point of view is what I see from my own phone.”

Real America shows the promise and limitations of vertical video

The vast majority of vertical video is recorded with phones, but the video industry hasn’t yet created good tools for professional shooters to work in tall orientation. One can theoretically rotate a standard DSLR camera 90° to use its full sensor vertically, but the metadata displayed on the monitor – camera settings, battery life - will be rotates and hard to read. The only camera that allows the user to rotate its display data 90 degrees for vertical shooting is GoPro’s Hero7 Black, according to pro video retailer B&H. That’s a tiny device obviously poorly suited for interviews or filming b-roll.

Technical limitations have driven video professionals like Aparicio to innovate. He creates footage for Real America using a Sony A7sii, recording in 4K. He applies tape to the screen of his Shogun Inferno monitor to provide a vertical frame in the middle. “I try to keep shots in the center,” he says. Horizontal images, like conversations between two people, are particularly hard to capture elegantly. But in the edit he’s found that vertical can allow for new and effective ways of creating shots, for example by stacking vertical wide shots of protests to tell a rich visual story. “I like that you can get a lot of information across quickly in vertical,” says Aparicio.

While it’s growing in popularity, even well crafted vertical video can inspire strong feelings — even hatred. Producer Christophe Haubursin selected a vertical format for a video Vox published earlier this year on skyscraper engineering, earning a million views on YouTube. But despite the video’s popularity, it received more than 3200 dislikes and a torrent of negative comments:

“cheap trick”

“I’m not watching on a god damn iphone”

“us iPhone users hate it too.”

Vox Video responded to their viewers in a comment. “We understand a vertical aspect ratio isn’t for everyone – don’t worry, it’s not something we’ll be doing often,” they wrote. “We took a risk by trying something new, so thanks for bearing with us.”

(One of my favorite vertical videos: the insightful and visually frenetic Internetting with Amanda Hess, which edited its first, wonderful season in vertical before reverting to the standard format for their second.)

Amanda Hess kills it on Internetting

Despite the hate, massive audiences are devouring vertical video on mobile apps, making it an attractive way to reach important audiences. The nonprofit Refugee.info creates vertical videos for migrants, many of whom rely on Facebook to communicate. “We explain jargon-heavy government info, connect them to service providers and simply try to listen and really understand what they need,” Refugee.info’s Maggie Piazza Carroll tells me. “Our photo, video and design work has to be clear, quick, accessible and engaging…Over 70% of our users view these videos on their phones, many via Facebook.”

Filmmakers also struggle to make vertical pieces that can appear on screens both large and small. Lynde hoped to play Lasting Marks at festivals, where it would be projected at large size in theaters, but also on tablets, laptops and phones. But achieving this flexibility proved to be a “main obstacle,” says Lynde. Because cinema screens are meant to show films in the horizontal format, Lasting Marks only occupied a quarter of the screen when it was projected at festivals, making it hard for viewers to see small details. For audience members sitting towards the back, the best way for them to see the key details shown in the documents…would be to watch the film streaming digitally, on their phones.

Next issue of TrueTube

The Weekly, by the Times, has premiered, joining efforts by Buzzfeed and Vox to create higher-production-quality video series that go in-depth to analyze the news visually. Next on TrueTube, I’ll be reviewing this new way of telling newsy stories.

Thanks for reading TrueTube. If you liked this issue of the newsletter, please subscribe and share with others who might enjoy my coverage!

Eli