TrueTube 5/2: Copyrights and copywrongs

A newsletter about nonfiction digital video from Eli Kintisch

By Eli Kintisch

In focus: New EU Copyright Rules

Video essayist Sage Hyden got a tough lesson this week: navigating copyright on YouTube can be treacherous. Regarding a video he’d made on military ads in Marvel movies, he tweeted:

The world of copyright online today is a foggy landscape…and yet the terrain is about to become still more uncertain. Changes are happening fastest in Europe, where two weeks ago the European Council voted 19-6 to approve a new EU law called the Directive on Copyright for the Digital Single Market.

The goal of the measure is to modernize copyright online. Despite that seemingly arcane issue, the fight over part of the law regarding user-uploaded content, so-called Article 17, drew millions of impassioned protestors online and in the streets of Europe.

Photo: (cc) by-nc-sa Tim Lüddemann • Protester: Emuolia Star

It’s not yet clear how, in order to comply, the multinational companies that control platforms like YouTube will change their rules on either side of the Atlantic. Established copyright holders like big media companies will probably benefit more from the new measure (previously called “Article 13”) than the hundreds of thousands of grassroots video creators. But the new law enshrines new rights for digital video creators in the EU – so the ultimate harm to European creators similar to Hyden (who’s Canadian) may not be so bad.

Hyden’s case illustrates how randomly the system typically works today, so in that way it’s worth looking at. (Hyden’s video had the infringing music embedded in a movie clip, apparently, and lots of people have used Warner Music’s songs in their videos – it’s never quite clear why some videos are flagged for infringement and others not.)

Crucially, the status quo places the burden to police infringements on the copyright holder. In this case, that’s Warner Music. As a user of YouTube’s powerful Content ID monitoring system, Warner received a notification that its content had been used in Hyden’s video. The company chose – probably via automatic settings, without a human making a decision – to notify YouTube that their material had been infringed, and that the platform should delete the video.

Which YouTube did. Among other options, Warner could have chosen to “claim” the video, allowing them to monetize the content and earn ad dollars from Hyden’s work.

Hyden says his use of the clip isn’t infringement, but instead amounts to “fair use” -- a concept we’ll get to in a second. He can decide now whether to dispute Warner’s claim. But had Warner opted to claim the video, Hyden could have chosen to keep it up anyway without its revenue, since he liked the audience attention it won.

That’s an important aspect of our current bizarre system, explains Hank Green in this helpful video. The state of internet copyright, he says, is less about law and more related to the policies of the tech platforms whose online policies stand-in for law. (The strongest example: while gifs usually rely on copyrighted footage, no one thinks that making or sharing a gif is copyright infringement.)

I spent way too much time choosing which gif — built with images belonging to NBC that nonetheless isn’t infringing copyright under our current norms if not laws — to place here

And he adds: “YouTube actually doesn’t want to stop copyright violation, and neither do the rights holders who own that content,” he says.

Why is that? Basically, U.S. safe harbor laws passed in the 1990’s meant that in terms of law, internet companies were platforms, and not publishers. As part of the safe harbor deal, platforms have created ContentID and other tools to monitor and remove infringing content as best they can. When you sign up to upload videos to YouTube, the fine print in the terms of service says that you, and not YouTube, are responsible for any copyrighted material you use. So YouTube essentially can’t be sued for the misdeeds of its users. And it would be financially foolish and legally infeasible for big media companies to chase down every infringer who posts their property online.

Copyrighted materials no doubt enrich YouTube’s offerings, whether its finely tuned analyses of historical fact or blatant theft of television scenes. Hank believes, and I agree, that the current policy “encourages creators to take…risks” and use such stuff. The arrangement has nourished an ecosystem of wonderful videos commenting on the news, critiquing pop culture, and remixing other videos. (And even more bad ones.)

And since the risks for creators are relatively minor – a video could be blocked, and if someone files a bogus claim one can challenge it, and – and there’s a whole ecosystem of great videos based on fair use of copyrighted material. (Though ContentID isn’t perfect — it’s even blocked NASA from using its own imagery, the appeals process is too slow, and companies routinely misuse it despite the threat of losing their Content ID priveleges.)

The vast, vast majority of disputes over copyright will never see a court. But our constant invocation of the doctrine of fair use reflects how we rely on language in the law to police the use of copyrighted works. That doctrine says that there should be an exception to a copyright if the use of the work is educational, or doesn’t harm the property holder’s business, or falls under other categories. YouTube doesn’t decide fair use claims. And yet the doctrine is the bedrock of so much nonfiction streaming video today.

Enter the new EU law.

Under the new system, the EU has decided that platforms, not users, are now to be liable for the copyrighted content they distribute. So instead of YouTube regulating the infringing content its users upload, the website will have to decide what content can and can’t be uploaded in the first place — at least in Europe, presumably. That probably will mean massive limitations on what YouTube will allow to upload. That’s why hundreds of thousands of EU citizens marched in protest against the measure, calling it an “upload filter” that will severely restrict what users can post.

As part of the EU “directive,” the new law now will require member countries to create national laws that dictate the actual rules of play within their borders. Some may be lenient, other stringent. But since tech firms don’t want to navigate a patchwork of different schemes, “there's good reason to believe that online services will converge on the most restrictive national implementation of the Directive,” says the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a key opponent of Article 17. For European creators, platforms like YouTube may simply block any copyrighted imagery from getting uploaded in the first place, or have users sign documents that make them legally liable for infringement.

But these dreaded “upload filters” may have big holes that users can exploit, says attorney Eleanor Rosati. In an article called The EU’s New Copyright Laws Won’t “Wreck the Internet,” she shows how the new law specifically creates not only exceptions for parodies, quotes, discussions and other uses of copyrighted materials, but the rights to use them. Here’s the text the EU has passed:

7. The cooperation between online content-sharing service providers and rightholders shall not result in the prevention of the availability of works or other subject matter uploaded by users, which do not infringe copyright and related rights, including where such works or other subject matter are covered by an exception or limitation.

Member States shall ensure that users in each Member State are able to rely on any of the following existing exceptions or limitations when uploading and making available content generated by users on online content-sharing services:

(a) quotation, criticism, review;

(b) use for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche.

(full text here, search “Article 17”)

So news reports, silly memes, or video essays that use copyrighted material: OK. Full clips from The Wire or Game of Thrones just uploaded to the site for free viewing? No.

Secondly, the new law “makes users’ legal position safer than what is currently the case,” Rosati writes in Slate (emphasis mine):

Platforms will need to prevent unlicensed content from being uploaded, but the law also says they might be liable if they unduly limit users’ rights. So, for instance, if you make a parody of “Despacito,” YouTube cannot prevent you from uploading it. If it does, and you live in an EU country, then you will have the right to have it reinstated on the platform.

So in exchange for strengthened copyright protections, users in Europe essentially got new language in law giving them new rights they could theoretically apply in court.

How would the Hyden case be different under the EU law? The current system allows Warner Music to select which infringing uploaders on YouTube it wants to stop. Under the new system perhaps YouTube could simply erect a filter preventing any Warner Music material from being uploaded to YouTube. Or Warner could negotiate a license up front. YouTube may choose to pay.

If they do, that could very well eat into the four billion dollars in ad revenue that YouTube earned last year. Hyden and hundreds of thousands of other YouTube users earn money on the platform with a share of that revenue. Ten years from now their ability to upload content may be reduced slightly, but the bigger impact could be cutting the revenue available to them on the platform.

A typically adorable frame from Kurzgesagt. Video

Creator focus: Behind the Scenes at Kurzgesagt

Few explainer channels have achieved the acclaim, and the polish, of German science and tech channel Kurzgesagt (koortz geh-ZAHGT.) Vivid, clear and funny animations, a large team of writers and artists, and perfect voiceovers give their videos a professionalism that’s rare for streaming animated videos. Whether it’s nuclear power, viruses or time travel, Kurzegesagt kills it on YouTube. Over the five years of their existence the channel has earned 8.7 million subscribers, more than 12,400 patrons and global attention, if not quite fame.

So how does Kurzgesagt do it? A recent minor dustup with another YouTube channel -- the details aren’t important, and they don’t reflect poorly on Kurzgesagt -- encouraged creator Philipp Dettmer to open up considerably on how they work. In this video the channel delves into their creative process…

…including how the channel conducts research, revises its scripts, and shares video cuts, as well as scripts, with scientists before publishing.

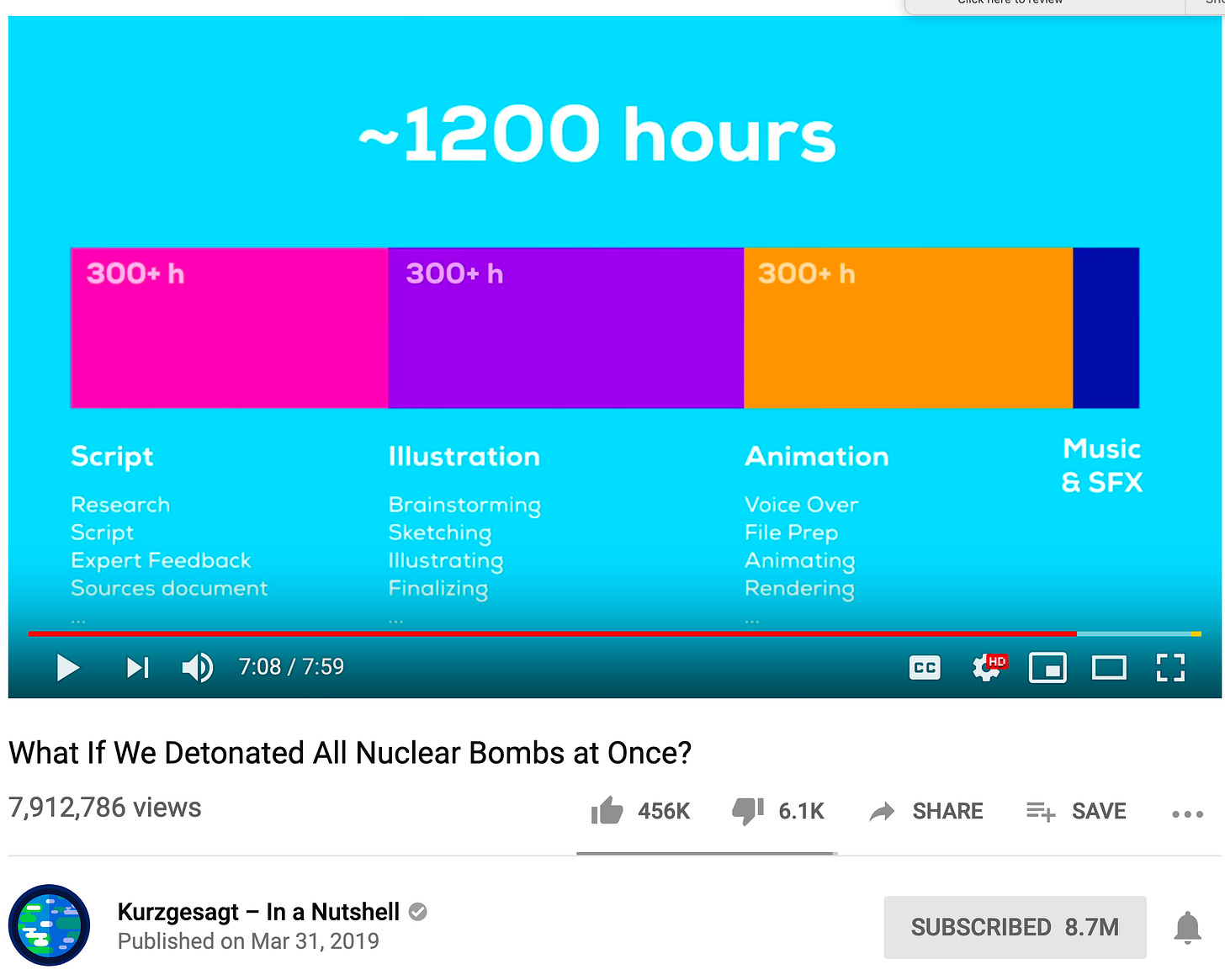

According to their Patreon page, they’ve invested more and more time per video as the channel has grown in age. “In 2013 an average video took about 150 hours. In 2015 it was about 250 hours. And in 2017 we spend around 400 to 500 hours per video,” the channel said then. Now it’s 1200 hours for each one:

This is a channel that prides itself, it says, on quality, not quantity. So maybe the best way to look at Kurzgesagt’s progress is to compare a very good video on the concept of time they made in 2013 with a “remastered” version that they uploaded five years later. I thought the original was great. But then they tightened the script and made even wittier animations. The first has earned 6.4 million views over six years. The second has garnered 4.7 million in less than a month.

As the channel’s creator Phillipp Dettmer readily admits, his team isn’t perfect. The recent imbroglio encouraged him to disavow two videos posted years before which they said they’d been unhappy with. One, with 31 million views, was a controversial take on depression. Another one, about the EU refugee crisis, bitterly criticized European governments’ policies. Both suffered, at the time, from insufficient research and revision, Dettmer said. Last month, they deleted both pieces (My links here are to reuploads.) “It is very hard to admit mistakes publicly, especially on something that was this popular,” wrote Dettmer in a Reddit AMA. But the channel emerged stronger from the incident, with more subscribers and respect. Kurzegesagt seems poised to continue to make quality, informative videos and earn money for it. That’s a rare combination on YouTube, where the economics mostly favor channels with tiny teams with one or two people. Like Vox Video, is this remarkable channel the exception that proves the rule?

Industry News

Highly recommended: Smarter Every Day’s Destin Sandlin’s recent three part series on the algorithms which control YouTube, Twitter and Facebook. His investigation focuses on how businesses and malevolent foreign actors manipulate these platforms, showing how “clickfarms” first amplify bad content until the algorithm starts feeding it to humans. “The internet is fake,” laments a researcher he interviews. “I’ve been doing this wrong,” laughs Sandlin. “I’ve been trying to make quality content.”

A doc you should watch

I didn’t expect this video about a woman attempting the land speed record on a bicycle to be as nail-biting as it was. (21min, Andria Chamberlain, Michael Kofsky 2018)

Tools

YouTube Studio is the new channel management site for creators, offering real time data for up to thirty videos, clearer lists of subscribers, a better dashboard and actual data on your thumbnail’s impressions. Useful resources for understanding it are here and here.

New bells and whistles in Adobe products: Alignment rulers in Premiere and content-aware fill in After Effects that you can use to erase whole objects from your footage.

Wikipedia can of course be an invaluable resource for research, especially finding primary or other secondary sources. But its editors often use extremely technical language. Which is why I often use the “simple English” version of Wikipedia pages. This article on the aurora borealis was extremely helpful recently...

1Password is offering free password management accounts to journalists.

Do you use Creative Commons? Yes, you use Creative Commons. Donate to them.

Video essay of the week

The fantastic literary essayists/jokesters at Wisecrack chastise J.K. Rowling for mucking up the Harry Potter cannon on her twitter feed:

Explainers of the week

I didn’t know that the gel doctors use during ultrasounds actually helps obtain a strong image:

And this one about diabetes is a solid explanation about an important disease that touches more than 400 million people worldwide:

Question of the week

Has Hank Green’s essential ICG Creator Chat podcast closed up shop? I’ve sent queries, but it’s not looking good since they posted their last episode in January. There’s been no reassuring mentions of the show on the twitter feeds of Green or the Internet Creator’s Guild, it’s ostensible sponsor.

The old episodes — they made 46 — are worth listening to if you’re trying to build a business with YouTube or want to understand how talented creators do their work. The show featured a wide variety of YouTube creators, and others, talking in depth about their creative processes, business strategies, and perspectives on the industry. Regular guest Anthony D’Angelo of the Internet Creators Guild shared important industry news each month, and the guests went deep with Green into their weekly routines, audience-building strategies and financial approaches. I’m guessing they didn’t find sufficient podcast audience to sustain it, which is a pity.

A similar show, Showmakers, also grew a devoted following but petered out. New podcast Rough Cut is strong; its a bit more about film-making than digital video per se…

Jobs

Washington Post seeks two video editors…Gimlet’s looking for a producer for its fantastic Every Little Thing explainer/science show…

Thanks for reading! Subscribe by clicking the link above!

-- Eli

Want to share a video or tip for the newsletter? @elikint at twitter, or email me at elikint@gmail.com.

TrueTube is a regular roundup of the best in streaming nonfiction video, including minidocs, explainers and educational channels. Inspired by Hot Pod, informed by my own tastes. About Eli: I’m a video producer and science journalist. Website Twitter Instagram